|

The Windermere Long-Term Pike Monitoring Programme

by Ian J. Winfield and Charles G.M. Paxton

(NERC Institute of Freshwater Ecology)

Recently, some angling media attention has focused on a long-term pike monitoring programme conducted at Windermere in the English Lake District by the Institute of Freshwater Ecology (IFE). Concern has been raised amongst some sections of the pike angling community over these activities, particularly in the light of a recent controversy over pike culling in Ireland. At the request of the Pike Anglers' Club of Great Britain and Ireland, this article has been written to explain the background and current operation of this research. In particular, we will take this opportunity to show that this scientific sampling currently has no adverse effect on the pike population in Windermere and that, in fact, the population is now more abundant than it has been for several decades.

First, however, we would like to emphasise that the current pike monitoring programme as conducted by IFE is not a cull, which is defined in fishery terms as a selective killing or removal of fish for management purposes. In fact, IFE has no management responsibility for the fish populations of Windermere or anywhere else. Rather, its remit is to research and monitor fish populations, and many other aspects of freshwater ecosystems, in order to gain a scientific understanding of their functioning and to enable their appropriate management by other organisations with specific management obligations. Consequently, much of the fish research undertaken by IFE is done so under commission to bodies such as the Environment Agency, the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, and English Nature.

The water bodies of the English Lake District, and Windermere in particular, are some of the most extensively studied and monitored lakes in the world. The resulting information provides society with an invaluable data resource for our understanding of the complex interactions of lake food chains, and important applied issues such as the enrichment of water bodies and global change. It is within this context that the 50+ year pike study, the only one of its kind in Great Britain and Ireland, has made a major contribution to our knowledge of pike ecology and management. Put in its simplest terms, the Windermere pike study is unique, invaluable, and respected by fish ecologists and fisheries managers around the world.

While the current pike operations of IFE at Windermere are for exclusively scientific purposes, they did originate from a pike cull undertaken during the Second World War and immediately thereafter. In 1941, an exploratory fishery for perch was initiated by the Freshwater Biological Association (FBA) to produce fish for human consumption. This proved successful and a commercial perch fishery continued on the lake until 1964, running alongside a traditional fishery for Arctic charr. In an attempt to protect and enhance the perch and Arctic charr populations, the feasibility of operating a small scale gill net fishery for pike was assessed in the winter of 1943/44.

During the above season, 88 pike were successfully caught and killed. Consequently, a much larger scale operation was begun in the following winter, the catch of which was carefully examined and documented. For each pike taken, biological information was gathered on features including length, weight, fecundity, and age. Incidentally, early assessments of the validity of pike age determination using scales and the operculum (gill cover) bone, and showing the greater reliability of the latter, were conducted at Windermere within this study and are now routinely applied elsewhere in Europe and North America. The assessment of fecundity by internal examination and age by examination of the operculum bone both require that the pike be killed. Such data acquisition has continued to this day, evolving from a management cull to an exclusively scientific monitoring programme.

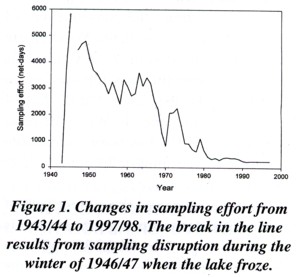

As the reason for the pike programme changed from a cull to scientific monitoring, the sampling effort was accordingly greatly reduced such that present levels are comparable with those of the exploratory fishing of 1943/44 (Fig. 1).

In 1989, responsibility for this operation passed from FBA to IFE. An extremely important point to appreciate is that the integrity of this long-term study has only been maintained by keeping its methodology unchanged except for this reduction in sampling effort. Thus, a given amount of gill netting set in 1998/99 will catch approximately the same number of pike as it did in 1943/44, as long as the abundance of pike has stayed the same. However, if pike had become scarcer in the lake, then the catch made by a given amount of netting would have decreased. Changes in the value of this catch standardised to a certain amount of sampling, or catch-per-unit effort (CPUE), are widely used in fisheries management to track changes in the abundance of fish populations.

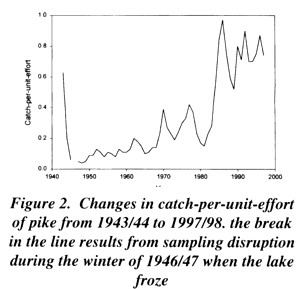

Fig. 2 shows changes in the CPUE of Windermere pike from 1943/44 to 1997/98. Following a dramatic reduction in CPUE in the first few years, testifying to the efficiency of the initial cull, there is a long-term upward trend. This indicates that pike are now more abundant than at any time since the winter of 1943/44. It is noticeable that a decrease in the pike sampling effort during the late 1960s, following the closure of the commercial perch fishery, was accompanied by an increase in pike abundance. Further reduction in the pike sampling effort was made by FBA on conservation grounds in the late 1970s after disease had killed 98% of perch, giving rise to fears concerning the consequences of this reduction of one of the Windermere pike's main food sources. Again, this reduction in sampling was followed by an increase in pike abundance. For the last 14 years, pike abundance in Windermere as assessed by CPUE has been comparable with that of the unculled population in 1943/44.

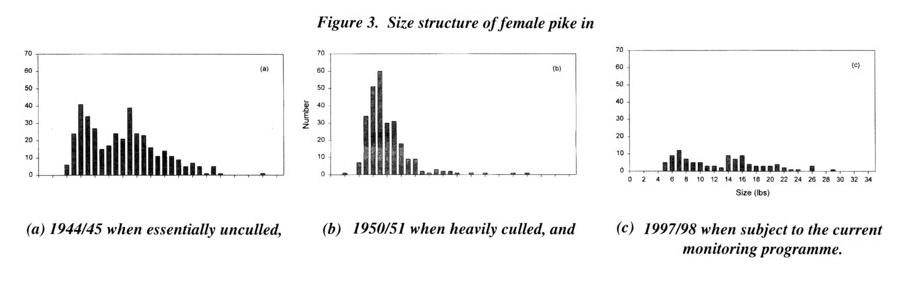

Further evidence of the current lack of impact of the monitoring programme is shown in Fig. 3 in terms of the size structure of the female component of the pike population. In the essentially unculled population of 1944/45, which had been only lightly fished the year before, a wide spread of individual weights was recorded with an average female weight of 11.2 lb and 8.9% of female fish weighing 20 lb. or more (Fig. 3a). In contrast, the heavily culled female population of 1950/51 had a more restricted weight distribution, an average weight of 7.6 lb., and only 1.5% of fish weighing 20 lb or more (Fig. 3b). The current female pike population as described using data from 1997/98 resembles that of the essentially unculled population of 1944/45, with a wide spread of individual weights, an average weight of 12.6 Ib, and 15.4% of fish weighing 20 lb or more (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, in recent years the average weights of both female and male pike have substantially increased. The Windermere pike population thus currently shows no significant adverse effects arising from the monitoring programme, whether they are assessed as population abundance or as individual size.

The pike monitoring is now conducted by IFE with a minimal sampling effort judged necessary to deliver the scientific objectives of the monitoring and results in a sample of approximately 100 pike from each of the lake's two basins. This total sample of approximately 200 pike may be viewed against our current estimates of a population of adult pike of 6,500 individuals. Gill nets are now set over a four week period in the autumn, subject to extensions forced by disruptions caused by poor weather, at four locations around the lake. At each location, a net is set twice for four days, during which it is inspected and any pike removed every two days. At any one time, four nets are set in the lake. Each gill net is 40 m in length, 3 m in depth, composed of 64 mm bar mesh multifilament netting, and is set on the lake bottom. All pike caught are either dead or immediately killed humanely, before being brought to the laboratory where they are examined in detail as described above. Although sampling effort is currently fixed, it is subject to constant review and should there be any indication of it causing a serious decline in pike abundance, it would be unilaterally further reduced by IFE. However, as shown in Fig. 2 this is far from the case and in fact, at the risk of overemphasising the point, the current monitoring of the Windermere pike population by IFE has no detrimental effect on its abundance.

In addition to concern over the effects of the monitoring programme on the pike population, which we hope have been allayed by the above information, some pike anglers have also expressed concern over ethical aspects of the use of gill nets. We do appreciate these concerns, but to put it quite simply we must either continue to use gill nets or the monitoring must be terminated. This statement is not made provocatively, but it is simply a consequence of the scientific needs of the sampling as we will explain further below.

The main reason behind the use of gill nets as the sampling technique is simply, that they always have been used. A key feature of the Windermere study, as emphasised above, is its long-term nature and in order to preserve continuity it is essential that sampling methodology is kept constant. Consequently, present day sampling is conducted using gill nets identical in functional terms to those first used in 1943/44 and the only significant change in methodology has been the reduction in effort described above. The latter change can of course be taken into account during analysis by the calculation of CPUE, but changes to the sampling gear itself would produce unknown changes in the catch. Consequently, although pike could be sampled from Windermere by alternative techniques such as seine netting, angling, fyke netting, trawling or even electrofishing in some areas, any resulting catches would not be comparable with those of previous years arising from gill nets. Similarly, quantitative echo sounding, although holding much promise for future application with coarse fish and currently used extensively by IFE to monitor salmonids and coregonids, is presently unsuitable for use with pike.

Any activity that impinges on a living fish must include a component open to ethical debate, and the use of gill nets is no exception. The Windermere study is essentially operated as a small, fully documented fishery in which humane considerations are given the respect that they deserve and are subject to review. After these and the above considerations, gill netting remains the only technique which will allow continuation of the long-term monitoring of the Windermere pike population. Furthermore, in our opinion, there is in fact no other sampling technique that could fulfil the requirements of a pike monitoring programme at Windermere. Even if such a technique did exist, a change to it would effectively end the present run of monitoring and begin a new series of data which would of course take another 50 years to approach the stature of the present data set.

Within the limitations of this article, space does not allow us to do full justice to the benefits accruing from the long-term monitoring of the Windermere pike population. Indeed, articles focusing on the knowledge arising from the study, rather than the study itself, are more appropriate for inclusion in future issues. However, one finding that may be of immediate interest to anglers is that the number of pike recruited to the population is strongly affected by the water temperature during the year in which they hatched, with higher temperatures leading to more fish. Consequently, good catches can be expected three to four years after a warm spring and summer, which is the length of time it takes a pike to grow to the size at which it becomes of real interest to the angler. While such relationships between temperature and recruitment are often the subject of speculation by fisheries managers and others, they can only be rigorously examined by the use of longterm data sets such as that collected at Windermere. In a more scientific context, further indication of the value of this work can be given here by noting that, together with work on the perch and Arctic charr populations of Windermere, it has contributed significantly to over 100 scientific papers, numerous commissioned reports to organisations charged with the management of Windermere, and several books. The study thus has importance not just to fish ecologists, but also to fisheries managers, legislators and owners around the world.

This article first appeared in Pikelines 81 (August 1998) - on this website 25/06/06

©Norfolk Fishing Network 2004 - 2026®All Rights Reserved.